Part I

INTRODUCTION- An SCA Approach To Using A Historical Style

The bulk of my terminology and techniques are taken from Italian and English, and use the teaching of Saviolo, which is backed up with older Italian styles of fighting. I believe that SCA rapier is a bit more of an art, than a sport, in that we can point to the books and say That's what we are trying to do. It's my contention that a Martial Art seeks to preserve the historical methods laid down in the past, with an eye toward trying to understand what was done and why. A sport, on the other hand seeks to win, given a set of rules in which the fight is structured. A sport, will not necessarily care where some move or other originated from, only that it works to score points; it can really be thought of as a science. Also, a sport will take and use what is effective, whether or not such move has any historical origin. Science continually changes as more observations are made, where the art may be seen as timeless in its scope. In SCA combat we can use either method to great effect. No one of them is by its self insular or superior.

In SCA combat, we are freed from having to accept in total the restrictions of combat imposed by various schools and masters and use what we feel works. It is up to the fencer to determine for themselves if they wish to simply win at a bout, or fight to prove some point of their art. I am presenting this work to try and impress upon the fencer that there were historical styles to fencing, and there is no reason that we cannot take from what we know was done historically and seek to apply it in a safe and enjoyable manner. I believe that to be authentic to one of the goals of the SCA, which is to educate about the Middle Ages; fencers should seek to define their style and approach to fencing with as much thought as we do garb and persona development. To this end, I would consider that the SCA rapier fighter should approach this work not as a definitive volume on English rapier, but rather a starter piece on how to use those influences from English rapier in your SCA fencing.

DISCLAIMER:

THIS IS NOT AN OFFCIAL SCA PAGE! Some of the pictures used on this site have been taken from other websites, but are of images of original texts, or are my own pictures. Other pictures are of friends who agreed to pose for the site. Content is my own. Any play you engage in is at your own risk, so no matter what, be safe. Always use safety equipment if attempting anything at full speed.

RELATIVE BACKGROUND OF FENCING IN ENGLAND

England was a country that was very traditional in its view of sword work. Sources on English sword work show that the English style was striving for its continued relevancy in the face of growing Italian influences in fencing, during the last half of the 16th century (Silver). Even though a continued interest in the rapier by the upper classes persisted, it is pretty much taken for granted that the middle and lower classes did not hold the rapier in much esteem. Indeed, it even seems to be an object of ridicule among traditional Masters of Fence in England (again, Silver). In England at the time, nearly every person from the lowest born to the highest carried a sword of some sort. This was primarily for the very practical reason of self-defense, since England was very violent, and quite dangerous to anyone walking about. The types of swords varied, but the fashion of a rapier persisted for the upper class, used as a means to settle questions of honor as well as practical self-defense. What sort of self-defending a rich, noble might have to do on their own behalf might be questioned, but if Silvers critique is to be believed, the habit of carrying a rapier had started to filter down to the class of not quite noble, not quite peasant.

Unlike Italy, where there may have been no stigma attached to carrying a rapier, and many more people did so out of custom, England was under no such restrictions of habit. Any man who carried a sword, should best be able to use it against whatever weapon was put about on him. In my research, I have concluded that there may not have been a very consistent fashion of the type of sword carried, but one was carried. The English appeared to have kept swords in circulation longer than the continent, so it would not be unusual to see broadswords, short swords and arming swords in possession along with rapiers; should one be rich enough to afford one. To this end, I do not believe that the very traditional method of Italian fencing was very popular amongst the English, until the very late 1500's and early 1600' s when the rapier was more socially acceptable and probably more available. Indeed there seems to be some indication that the English did not use the rapier in perhaps quite the same manner as the Italians, having considered the Italian method of rapier fighting as being perhaps novel This may explain the late take up of the rapier. This idea may best be summed up in a glance at the differences between "Italian" schools of Fabris (1544-1618), vs. Saviolo (1590-1599).

Saviolo was Italian, and was purportedly from the Padua area, much like Fabris, and had undoubtedly learned rapier first in that region. However the two styles of Fabris and Saviolo could not be further apart in ideology. Meaning, the typical Bolognese styles may hearken back to Morozzo, Di Grassi, Manchalino and Agrippa, but by the late 1600's the Italians had evolved their rapier style to be very orientated to the thrust, and relied on some very interesting and quite difficult body postures to use effectively. Saviolo's method would resemble the Morozzo, Manchalino and Agrippa methods far more in casual observance than Fabris did, even though they both borrowed from the same root sources and used similar rapiers. Ultimately, it was the culture and the location in which they perfected their styles I feel had the biggest influence upon them.

Saviolo it seems felt free to take what he thought was valid points from many sources and apply it to the given reality of current English fighting, just as Fabris perhaps did for the people in his own time and place. It is believed that Saviolo and Jeronimo before him had been teaching in London since the early 1590's. This paper will include references to Saviolo, Morozzo, Agrippa, DiGrassi and Silver. I have my reasons for including Silver in this work, mainly because he represents what we believe is the "contemporary" form of English sword play that co-existed with rapier. Silver provides a good use of contrast to help understand what the mentality may have been at the time.

So, why do this?

Why are we in the SCA in the first place? Is it to play at a sport with trappings of something historical, or is it to get a better understanding of arts and sciences of times long past? The fun sport like aspect of the SCA does tend to be attractive and draw people to it, but once you do this for a while, you might ask yourself, "OK, I get that we wear funny clothes, but why did THEY wear these funny clothes?" The SCA is not a fantasy fiction organization, and in more advanced areas of the SCA, they like documentation. We do this for an appreciation of history. We get curious about the details. Once we ask what it is we do, we then ask why, and then how. Documentation can tell us a great deal of what, and how, but the why is the most important. We spend a lot of time with garb, trying to nail down the right look for the right time, but why then would we ignore the fighting? SCA fighters have usually relied on word of mouth, maybe a few classes, or even some instruction in Olympic style fighting. Unless any of these sources actually can back up with documentation of what was done where and why, it suffers from a little too much creative application of the art. That is not to say it is not effective, but if we review the historical texts, we'll find out that there are a few things we do the same way, and a lot we don't. It's very interesting to figure out why that is.

I like to say that this is like doing civil war re-enactment (who are very strict on documentation), but then using modern squad level tactics to fight on the field. It wasn't done. We put a lot of time in trying to look, act and understand the persona's that are developed for a good SCA member, but why ignore the fighting? Re-discover what was done. It's a very fascinating journey and it can serve you better when your local resources can't add new dimension to your fight. Get out to some WMA events and see what other non-SCA people do with this kind of combat too. There are a lot of people doing this now, and it's very fun to compare notes.

|

|

|

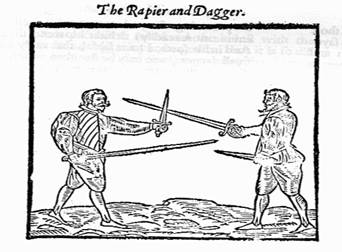

Illustration from Saviolo |

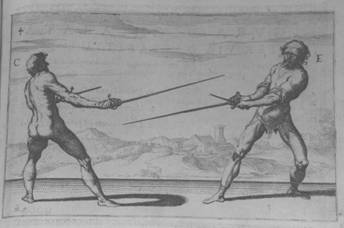

Illustration

from DiGrassi |

Illustration from Capo Ferro

|

PICTURING THE FIGHT

So, what did it look like? The English style, such as it was, was probably a mish-mash of Italian, Spanish and English sword styles. Saviolo was not the first teacher from Italy in London, but he was the only one that apparently was published until the early 1600's. In order to understand this style, it's best also to understand what it's not. By using Silver as a method of contrasting, we can get a better look at what it might have been like, and how it might have been used practically. Saviolo was also kind enough to put wood cuts in his manuscript so that also helps. The style was upright, close measure (as opposed to what modern fencing and period Italian fencing would be comfortable with), much like Silver, but with more movement. Saviolo said to move the foot with each strike, just like Morozzo and unlike Silver. He advocated strong defenses, but fluid movement. Much like what a boxing match might look like in 1900. Up right backs, hands out front, feet moving here and there.

Silver, by contrast had advocated a very static stance, with strong purposeful steps that followed the sword blow. There does not seem to be a lot of running backwards in the English sword fight, which may have been a cultural as well as a practical matter. Whatever it is, I am deliberately not advocating such actions in this work. Most of all of the movement here will be forward in direction. Saviolo reflects this by being a strong believer in side steps and passes. The purpose of not backing up in a fight is a very key understanding to how the rest of this instruction is presented DO NOT BACK UP. Backing up in a duel of honor may instantly invalidate the argument for which the fight is occurring. It displays fear before the opponent and shows a lack of willingness to "Take it like a man" as it were. Removing oneself from a fight as a means of defense would be considered a poor display of skill and lack of understanding of how to handle a fight. Rather, maintain a safe measure, but instead of removing from a fight, it would be practical to instead use that time to gain control of the opponent's blade. Not run from it.

In fighting, thrusts would be quick, to the face or the lower belly, with blazing fast wrist and elbow cuts to the head, neck, knee, or other vulnerable spot if needed. Since these cuts would be either true edge or false edge, there would be little "Wind Up" as it were to deliver a strong true edge, body cleaving blow, as might be common with Silver But, the direction of the cut might follow the same path and have the same target. Saviolo was good for either open hand or dagger, and a variety of other items, but had a particular fondness for the dagger, in contrast to the stout English buckler carried at the time. The buckler was a universal item used by many English that might have very well died out on the continent, so Saviolo's dagger was probably very novel for its time.

THE LESSONS

The lessons here are meant to build on one another. It is important that when working with these lessons, that you don't try to re-invent the basics that are being demonstrated. If for example a lesson calls for a pass, do so with the same technique used in the prior lesson that may have covered that. Improvisation is acceptable in any lesson (once the initial concepts are understood) but try to keep to the theory of this work, meaning; keep it in context. Also, feel free to read the original works by period masters for further insight to concepts used. Everyone has a different interpretation and might very well bring something to the body of knowledge that was not understood by others. It is the goal here to have these lessons relevant to the SCA fight, so if you were to try to use them in a generic WMA format, you might have problems. Please keep that in mind.

Also, drills here should be approached as being the ideal condition. Will the movements and things being exemplified in the drill actually occur just like that? No, probably not. It is rare that you will find a textbook response to an action. Start with the greater, higher level of what the point of a drill is, and layer on the nuances. It will not all come at one time. When you start these learning points, it is a path of discovery of movement and tempo; expectation and reaction. What will work for you may not be what works for others.

RULES OF THE ROAD

Grasping these concepts before going further will be very important to using this style. The foundations that are noted here are relative directly to the fight of Saviolo. It is important to understand that Saviolo is using method since it has direct bearing on what he is espousing. Keeping this in mind, respect your prior experience in fencing, but try to hold to what is being offered here since it could be different and may not feel comfortable. Also, it will probably contradict itself from time to time and also directly conflict with what might be known as "Modern" fencing. This is normal.

Stance: In the SCA we do much of our practices on nice gym floors, but most of our fighting in dirt and grass. This means that we just can't use the same moves developed on controlled surfaces like wood or cement floors that Olympic fencers do. So, long lunges are pretty much ruled out. Don't ever rely on them to make your touches. If you practice to rely on long fast lunges, you'll be finding yourself handicapped when you fight in 12 inch grass after a heavy rain.

Sword Presentation: Always be ready to receive an attack. Even if the opponent does not appear to be in measure.

Agent and Patient: In some historical texts, the sword play is described between two parties. Agent is typically the one who is representing the nugget of the lesson, and the Patient is there to represent outcomes from the act. In conducting drills, do the same thing. The most important part when conducting Agent-Patient play is to keep it in the scope of the lesson, and to not mess around with the point of the lesson. Meaning, if the play calls for the Patient to receive a hit, get hit. Even if you know darn good and well you can avoid it. The Agent has to learn how to accomplish a successful point of the drill. Your roles will change, and you will get a chance to return the favor.

Defense: First and foremost, consider yourself passive. You should always assume to act in defense first. This is the "Art of Defense" after all. Don't enter into a fight first thinking about your attack.

Line: Always seek to close the line. Even out of measure. Understand the direction an attack can come from and actively work to deny that from the opponent.

Wards: Saviolo says to always "Stand on your surest ward", meaning, no useless movement. Don't bounce the blade; don't waste motion, or tempo. Don't waste movement in measure. At the start, your movement should only be done to close the opponent's line of attack. This is critical. What moves in measure is the first thing that might be hit.

Thrusts and Cuts: You must always observe this

rule with thrusts: extend the point first, and follow with the

foot. The foot lands the tip. Not an extension of the arm

to the target. You must always observe this rule with cuts: Cut

only at the speed of gravity + a little. Both of these rules need

to be locked into your understanding of every single lesson shown

here. It will be implied in every drill. Doing anything other than

this can cause unsafe play. NOT GOOD.

Points to Emphasize

- If you are unable to hit the opponent safely, then you do not hit. SCA rules must always stress safety first.

- Keep your weight on your heels, not on the balls of the feet. Use a stance, about 80/20.

- Be aware of your foot placement. Don't cross the feet and don't get too narrow at the foundation

- Always set yourself back to neutral after every movement, or at least don't get so strung out on your movements that you end up with your balance thrown off, your head down around your waist, and your shoulder higher than your nose

- Learn to move backwards, forwards, side to side as fast as you can.

- Make sure your steps are not any wider than maybe 1 x times the width of your shoulders.

- Only move when you need to. Useless movement for the sake of just moving will get you killed. Initiating tempo in distance will trigger an attack.

- Keep your back straight. We use a concept called a "Cone of Balance". Simply put, this is wide base - narrow top; many people will start fighting and end up with a narrow base, and a wide top. This would look like your feet close together, your head leaning way out over your waist, arms extended as far as you can go. This is bad.

- The foot always follows the tip of the sword. Start every single thrust with the blade first, letting the tip pull the body after it.

- Cuts occur at the speed of gravity + a little.

- Make all turns of the sword in front of the body. This can be thought of as keeping the meat behind the steel. Don't put the meat in front of the steel.

Terms used in this work

Any relative terms and concepts that are being used will be noted in part IX "Terms".