Part II

PRESENTATION OF THE SWORD

How to hold and present the sword

First off, let's look a bit at what the intent is of how you are standing. I refer to this generally as presentation or presenting the sword. You want to approach the fight with as much caution as possible. ALWAYS start out of measure. ALWAYS assume the other guy is better, faster and smarter than you are. Better a pleasant surprise than something worse! Historically, we are looking at what amounts to an honorable fight between educated men of means. Men who paid good money to associate with a school or a master, so we are really talking about professionals here. There shouldn't be an element of fear in what you are doing or why you are there, so first understand that if you are terrified, you will probably do a lot of things wrong. There is nothing natural or normal when it comes to sword fighting. Normal people don't do this, it's not natural to lean in to a cut, and the foot work is something you have to train at. What this means for you is that you need to train out normal habits and such. As an expert professional fighter, you would be expected to have been drilled into exhaustion and muscle memory reactions would probably be the norm. Your untrained and "Natural" reaction is probably the worst option for you.

Saviolo talks about "Standing on your surest ward", but he does not talk about the idea of being an agent or patient. He does provide examples of behavior that to me indicate he prefers a reactionary response, which makes most of his fight from the patient's perspective. I take this to mean that he would rather let the opponent initiate tempo and use it against them. But what if you want to attack? What if you don't want to be defensive? You would then consider yourself the "Agent" in the exchange. However, you must first enter into the fight as the patient.

There is yet another thing we can look at historically, and that is in some cases in a fight, one person has right of first strike and the other is set to defend. Much like any football match, one side is offence, the other defense. There are merits to each of the wards used by Saviolo, you should first understand if you are set up to defend or offend, and select the ward that will best suit you.

If the conclusion to attack is made, you'll then be looking to set your ward accordingly. Some grips are better at things than others, so getting a grip on your grip is the next thing to consider after you determine if you are defending or offending.

Putting the sword in the handVulgar Grip: This will be a single finger in the ricasso and the thumb along the edge, where the thumb can be used to guide the cut. This grip is referred to by Saviolo as one that he does not advise to use. There is some discussion in his work about what not to do, and from that it would appear that many Englishmen preferred this grip. I actually like this grip as it provides edge definition on cuts. Saviolo does not like it, preferring the more commonly used Key Grip that most Italians preferred at the time. For using Saviolo's method in SCA combat, the action from the Vulgar Grip might be a little slower, which is fine, as it means the cuts from it might not land as hard

|

Key Grip: The second method similar to the vulgar grip is the key grip, only instead of a thumb on the false edge side of the ricasso, it covers the fingernail of the index finger. Saviolo preferred this grip. It can also be with the index finger slightly pointing down the blade, but in all cases, thumb and index finger are primarily used to hold the sword. Its use comes in when doing cuts where the sword kind of twirls around.

|

SCA Grip: Yet a third method is not mentioned by name in the historical text, but has become common in the SCA practice is to use two fingers over the ricasso. This method gives a little more point control, and is not well suited to cutting. I also find this more useful than a key grip, and a fair method with a lighter sword. Saviolo does not particularly care for this grip.

|

Always Start in terza

The most general staring point will be Terza. Saviolo has a few different variants of this position, and it would seem most of his stances are based off of it. It seems to be pretty well adopted by the SCA, and its descendants are seen in modern Olympic fencing. Commonly, the position is thought of as low extended ward, or broad ward. The historical reference here would be codelunga alta.

|

|

|

| Saviolo, broad ward | Cappo Ferro, low ward | Sweatnam, terza |

"V. For your Rapier, holde it as you shall thinke most fit and commodious for you, but if I might advise you you should not hold it after this fashion, and especially with the second finger in the hylte, for holding it in that sorte, you cannot reach so farre either to strike direct or crosse blowes, or to give a foyne or thrust, because your arme is not free and at liberty.

L. How then would you have me holde it?

"V. I would have you put your thumbe on the hylte, and then the next finger toward the edge of the Rapier, for so you shall reach further and strike more readily. "

Sword in Terza

|

Notice the wrist here, how it's held in such a way that a wrist snap might very well be coming. In period, cuts were done more than what one would find in a typical SCA bout, but it was not common or expected to lead an attack off with a cut. In these times, some hilts are even quite open, which leads to the conclusion that the hand may not have been a target of choice for a thrust, but only a secondary target for a cut. If you were to fight SCA styles with the wrist cocked, and come to find yourself with your wrists in distance, it will lead to arm sniping. Instead, if you make an engagement, and you move to a middle measure or a good inside measure be sure to make the best use of the hilt to protect the hand. Terza is pretty much a founding presentation in all forms of fencing, but it has evolved over the years. Don't use the modern version. Terza is loose, with the wrist ready to deliver a cut or cravasion. In all cases, there is not a straight line from the tip all the way through to the elbow.

| Modern foil (Don't do this with a Rapier!!) | |||

|

If you have a mirror, look at your profile when holding the sword with your wrist cocked, and then line the blade up with the forearm, tucking the pommel into the hollow of the wrist, and then observe your profile. You might see that a good back of the hand, wrist target area has just disappeared and the harder to hit elbow or upper arm is the closest thing to the opponent. Notice how there is a straight line from the tip all the way through to the elbow. Notice the differences with the above historical plates. A loose wrist leads to more cutting options. In historical play, the quick cuts are the defense action. It also means that you could be more exposed on the hand!!! If you do decide to lock the arm up, it becomes an entirely different kind of fighting style, more like modern fencing. The majority of movements there are made with the elbow only. While this may be more protective, and definitely is in keeping with more modern concepts, the rapier is a different weapon and has a great deal of more weight to it than a foil. Long term use of this type of presentation can lead to chronic elbow damage, and I don't feel this is appropriate for a rapier | ||

So, warts and all. We know that there are more modern ways of doing this, but they are not Historical. In using the Historical example, takes away from interesting nuance and logical flow of movement. While it may be safer from a hit perhaps, it's not physically of much benefit over the long run. The rapier is not a foil. Don't treat it like one.

Yet another concept that is lost with modernistic stances is the half tempo cut that is used for a defensive action. Closing a line is all well and good, and is used in much of the historic play, but it's not always a good opening in a pass. One of the basic concepts in rapier play is to take the momentum of the opponent, the tempo; and use it against them. Half tempo cuts used here would be the falso dritto and the falso manco, half dritto or half riverso. You can even do a falso tondo or a falso roverso tondo. Heck, go full on experimental and try a falso fendente. A loose wrist is needed for these actions.

Also included in this section are the remaining concepts for how to present the sword. Remember, these are quite often literal positions to be in, and can be generalized reference points. Agrippa was kind enough to simplify these often varied and wild positions that swords were held in. You might also hear this as a Presentation, or On Guard. Saviolo would call it your "Surest Ward." Whatever the term, it refers to where the fighter has their sword when facing an opponent.

From Agrippa, we are going to use the following terms for where to hold the sword. Everyone else back then did.

| Prima (First): Sword is held with the true edge up (see below) above shoulder height point in the face of the enemy. Keeping the point in the face is a good idea at all times. It's generally called menacing when you do this. | |

|

|

| DiGrassi, Sword in prima | Sword held in prima |

| Secunda (Second): Sword at shoulder height palm down quillons horizontal to the ground, arm straight. | |

|

|

| Fabris example for secunda | Sword held in secunda |

| Terza (Third): Sword held in a "hand shake" like position. Elbow near the lower rib cage, thumb on the upside. Elbow is bent, wrist cocked somewhat, point, menacing | |

|

|

| Saviolo low ward, in terza | Sword held in Terza |

| Quadra (Fourth): Arm across the body, hand extended out, at mid chest level, palm up. Point Menacing. | |

|

|

| Swords in Quadra From the French Manual d'escrime 1877. Both should be in fourth | Sword held in Quadra |

Again, these are reference points. Some of the parry positions will be the exact same as these positions but I'll be sure to note that.

Also, these terms are in keeping with the Saviolo inspired method here. These terms were used by him, and probably quite well known as standards in the common body of knowledge. Agrippa published his works around 1558, so there was about 40 years for these ideas to circulate by the time Saviolo wrote his works. For ease of teaching, however, I will also annotate actual parry positions that would be in keeping with the concepts that Saviolo advocated. It will be important to note that Saviolo's manual, like most of that time, may be a little foggy when it comes to what the actual parry might have looked like. The 8 parries shown later are actually an amalgamation of the given classical parries from the 16th century. Keep in mind too that there was a wide division between fencing masters about what parry should be used when. For example, DiGrassi has 15 different parries/positions, and Agrippa has 4. Saviolo seems to be in agreement with Agrippa that most positions should be relatively simple. Interestingly, Saviolo has one set of methods that he speaks to that seems right out of Agrippa, while another approach he has seems to be in keeping with older "Dardi School" style of fencing. I feel that it is fair to borrow from what we know the older styles did when using Saviolo's work. His background would have certainly covered the traditional Italian styles, so what he is using here is going to be based off of it.

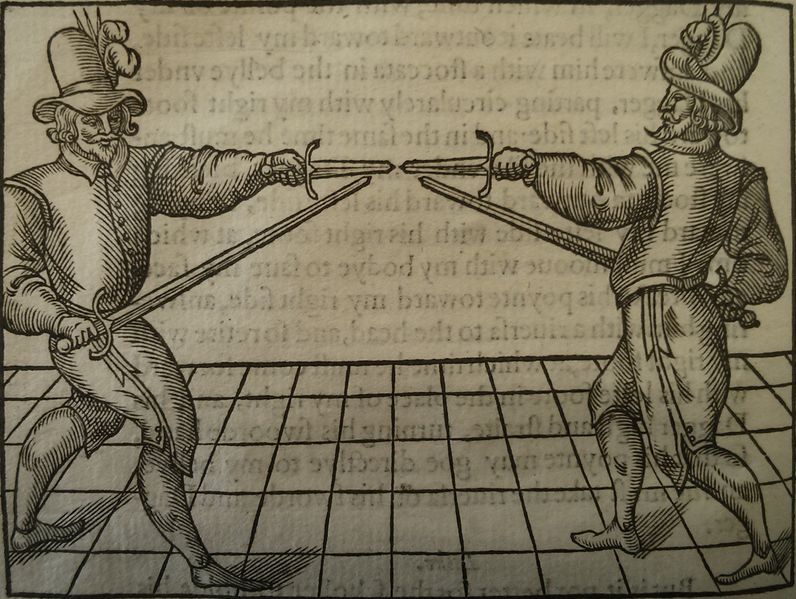

Saviolo uses three distinct wards in his work. I will refer to them also as First Ward, Second Ward and Third Ward. First and Second ward are similar in terms of how you will receive an attack with either passive or active dagger, but the fighter is going to be waiting it out for the opponent to initiate tempo. These are similar to the "defensive" stances used in other historical play. In first ward, the sword will be used to beat away the opponent in the same time that the dagger might make a control, or a parry replace is used. Second Ward can use both left or right foot forward, however the intent of the fight is different. In using Second Ward, the dagger only defends, the sword only offends. Distance is hidden by the body posture. Third Ward looks more offensive in line with Bolognese style, where the fighter is using an active/attack position, maybe looking to counter long thrusts perhaps.

- First Ward: Sword held in Broad Ward. First is Active Dagger, second is Active Hand.

- First Ward: Sword held in Low Extended Ward. Dagger is passive.

"V...he shal cause him to stand upon this ward, which is very good to bee taught for framing the foote, the hand, and the body: so the teacher shall deliver the Rapier into his hand, and shall cause him to stand with his right foote formost, with his knee somewhat bowing, but that his body rest more upon the lefte legge, not stedfast and firme as some stand, which seeme to be nayled to the place, but with a readines and nimblenes..."

"V...he shal cause him to stand upon this ward, which is very good to bee taught for framing the foote, the hand, and the body: so the teacher shall deliver the Rapier into his hand, and shall cause him to stand with his right foote formost, with his knee somewhat bowing, but that his body rest more upon the lefte legge, not stedfast and firme as some stand, which seeme to be nayled to the place, but with a readines and nimblenes..."

The second ward is right out of Agrippa. Point is well back in Broad Ward, the dagger only defends and the sword only offends. When using this stance, distance is hidden by the use of the sword in Broad Ward. If the dagger is able to pick up the opponent's sword, the opponent is easily within thrusting distance. Saviolo's engagement distances were much closer though.

Second Ward: Sword held in broad ward, left foot forward, dagger active "V. Therefore I saie, when you shal stand upon this ward, and that you be assailed and sette upon, keep your point short, that your enemie may not finde it with his, and look that you be readie with your hand, and if he make such a false proffer as I spake of before, you being in the same ward & in proportion, may with great readines put a stoccata to his face, shifting sodainly with your left foot, being a little folowed with the right, and that sodainly your Rapier hand be drawen backe."

"V. Therefore I saie, when you shal stand upon this ward, and that you be assailed and sette upon, keep your point short, that your enemie may not finde it with his, and look that you be readie with your hand, and if he make such a false proffer as I spake of before, you being in the same ward & in proportion, may with great readines put a stoccata to his face, shifting sodainly with your left foot, being a little folowed with the right, and that sodainly your Rapier hand be drawen backe."

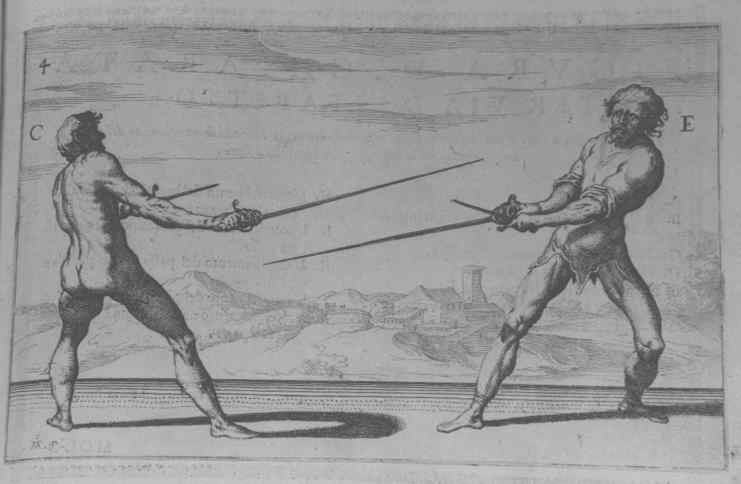

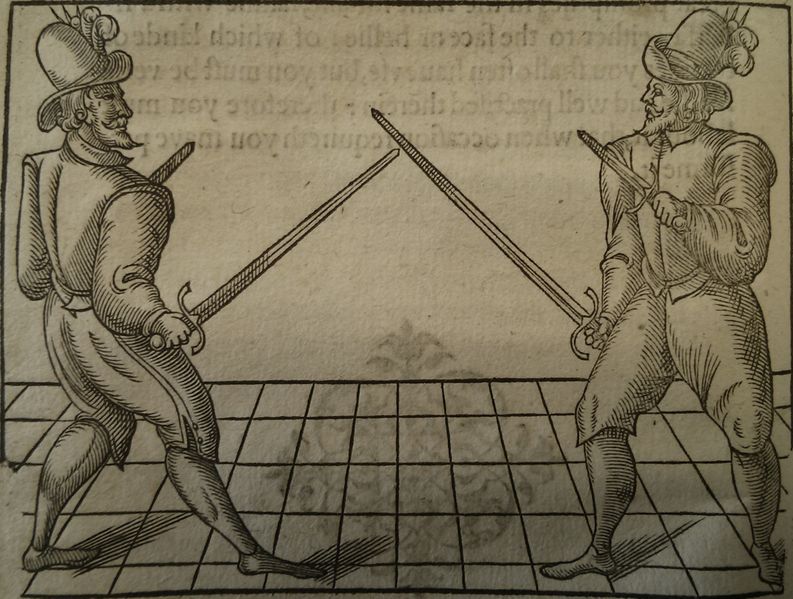

The third ward from Saviolo's description sounds like a very similar ward in Agrippa at the start, but in looking at the plates associated with the ward, it would appear to shift to a ward more suited to cutting. In the end, it looks a lot like a typical Italian DiGrassi attacking position. Check out the fencer on the right. It was not uncommon to classify a fight into either "Defend" or "Attack" mindsets. While the first two types of wards used here are really good at being patient and letting the opponent initiate tempo, the third ward is more attuned to causing the tempo. Further, this is a very good sidesword kind of stance, in that it guards well against an opponent who likes to open with cuts. There is no depiction of this stance with a dagger, but I would assume it is probably similar to any typical of Italian method. Further, from Cappofero, we know that the initial entry is well back, with the weight on the trailing foot, and as the line closes and the measure narrows, the fencer who will start the attack will switch to an attack stance, which will move the body to one where most of the weight is over the lead foot, with the intent to pass from the hind foot forward or push deeper into a lunge. This might be seen with DiGrassi's stances when using a buckler or rotella.

Agrippa also has a similar Terza ward much like what I think Saviolo is picking up on. However, there is no picture from Saviolo depicting it, but there is descriptions where the fencer moves from a narrow stance into this stance in Agrippa's work. It starts with the feet narrow and sword short, much like what Saviolo is noting, but goes to what I think is the plate associated with his Third Ward from his book. Use this ward if you are looking at a cutting fight. It's very useful for cutting because it keeps much of the steel as far away from the defender as possible. In a cutting fight, you will want to get as much steel in front of a cut as you can. It looks like Saviolo is saying that you would assume a thrusting attack, and counter, and if that's not the case, you would step to this position if your opponent is likely to cut, or you wish to cut. Because of this, I often refer this presentation to being useful for attacking as well, if the opening attack you wish to throw is a cut. It also defends well against an attack, which needs to be closer to the body in executed tempo (hence the best reason to have as much steel between yourself and the opponent, cutting off the arc of travel a cut would take).

- Third Ward: Guy on the right, sword shown held in third ward without dagger. The second plate is an example from Meyer, probably a little more aggressive in stance than Saviolo, but similar in intent.

"V. I have alreadie shewed you of that importance & profit the two former wardes are, as well for exercise of plaie, as for combat & fight, if a man will understand & practise them. Now also perceiving you so desirous to go forward, I will not faile in anie part to make you understand the excellencie of this third warde, which notwithstanding is quite contrarie to the other two. Because that in this you must stand with your feet even together, as if you were readie to sit down, and your rapier hand must bee within your knee, and your point against the face of your enemie: and if your enemie put himselfe upon the same ward, you may give a stoccata at length betweene his rapier and his arme, which shall bee best performed & reach farthest, if you shift with your foot on the right side. Moreover, if you would deliver a long stoccata, and have percieved that your enemie would shrinke awaie, you may, if you list, at that verie instant give it him, or remove with your right foot a little back toward his left side, and bearing backe your bodie, that his point may misse your bellie, you maie presentlie hit him on the brest with your hand or on the face a riverso, or on the legs: but if your enemie would at that time free his point to give you and imbroccata, you may turn your bodie upon your right knee, so that the said knee bend toward the right side, & shifting with your body a little, keepe your left hand ready upon a soddaine to finde the weapon of your enemie, and by this meanes you may give him a punta riversa a stoccata, or a riversa, to his legs. But to perform these maters, you must be nimble of body & much practised: for although a man have the skill, & understand the whole circumstance of this play, yet if he have not taken paines to get an use and readines therein by exercise, (as in all other artes the speculation without practise is imperfect) so in this, when he commeth to performance, hee shall perceive his want, and put his life in hazard and jeopardie

"V. I have alreadie shewed you of that importance & profit the two former wardes are, as well for exercise of plaie, as for combat & fight, if a man will understand & practise them. Now also perceiving you so desirous to go forward, I will not faile in anie part to make you understand the excellencie of this third warde, which notwithstanding is quite contrarie to the other two. Because that in this you must stand with your feet even together, as if you were readie to sit down, and your rapier hand must bee within your knee, and your point against the face of your enemie: and if your enemie put himselfe upon the same ward, you may give a stoccata at length betweene his rapier and his arme, which shall bee best performed & reach farthest, if you shift with your foot on the right side. Moreover, if you would deliver a long stoccata, and have percieved that your enemie would shrinke awaie, you may, if you list, at that verie instant give it him, or remove with your right foot a little back toward his left side, and bearing backe your bodie, that his point may misse your bellie, you maie presentlie hit him on the brest with your hand or on the face a riverso, or on the legs: but if your enemie would at that time free his point to give you and imbroccata, you may turn your bodie upon your right knee, so that the said knee bend toward the right side, & shifting with your body a little, keepe your left hand ready upon a soddaine to finde the weapon of your enemie, and by this meanes you may give him a punta riversa a stoccata, or a riversa, to his legs. But to perform these maters, you must be nimble of body & much practised: for although a man have the skill, & understand the whole circumstance of this play, yet if he have not taken paines to get an use and readines therein by exercise, (as in all other artes the speculation without practise is imperfect) so in this, when he commeth to performance, hee shall perceive his want, and put his life in hazard and jeopardie

Public domain images lifted from Wiktenaur HEMA page

Points to emphasize:

- Some grips are better for thrusting than cutting

- Some grips can't be done at all, depending on the make of the hilt, size of hand, etc.

- Always wear a glove when holding the sword

- Use whatever grip is most comfortable, just not one that creates more risk of being hit

- Changing a grip, as in moving the second finger to the ricasso to change a balance point, can be done during a fight, or when just moving. That is OK

- The primary starting position will be Terza

- These presentations are starting points of the fight